African-American history of Henderson County, Part Two

- Missy Schenck

- Feb 4, 2021

- 10 min read

Updated: Mar 11, 2021

The Society of Necessity

By Missy Schenck

What Happened to the Promised Land?

The dissolution of the Kingdom of the Happy Land was gradual. Work was a driving force, and residents began to drift away to nearby Hendersonville, Flat Rock, Spartanburg and Greenville. In the end, there were not enough people up there with cash to pay the taxes on the land. By 1900, few, if any, remained. Today, the only signs that people of the kingdom lived on this property are an old chimney, piles of rocks and remains of an old cabin.

Eventually, Henderson County confiscated the property for back taxes. Around 1910, Joseph Oscar Bell, one of the founders of Tuxedo and the Green River Mill, bought 325 acres, including the kingdom, on the courthouse steps. It was land his family enjoyed for more than a hundred years.

Many legends exist about the Happy Land, including the general one that kingdom members brought wealth, silverware and gold with them to their new mountain home and hid it in chimneys and graves. Word spread of this legend, and fortune seekers destroyed the cabins. The Bell family later razed the derelict dwellings.

In the late 1950s the city of Greenville forced the Bells to sell 75 acres on the South Carolina side for the new Greenville watershed. The remaining 230 acres stayed in their family until about four years ago when they were sold to Kingdom of the Happy Land Farms, LLC. Kingdom Farms’ goal is to establish a stronghold in the thriving hemp market. Owners Shelle Rogers and David Payne live on the property and have extensive experience in growing and cultivating hemp for their award-winning full spectrum hemp extract and CBD oil.

The Society of Necessity

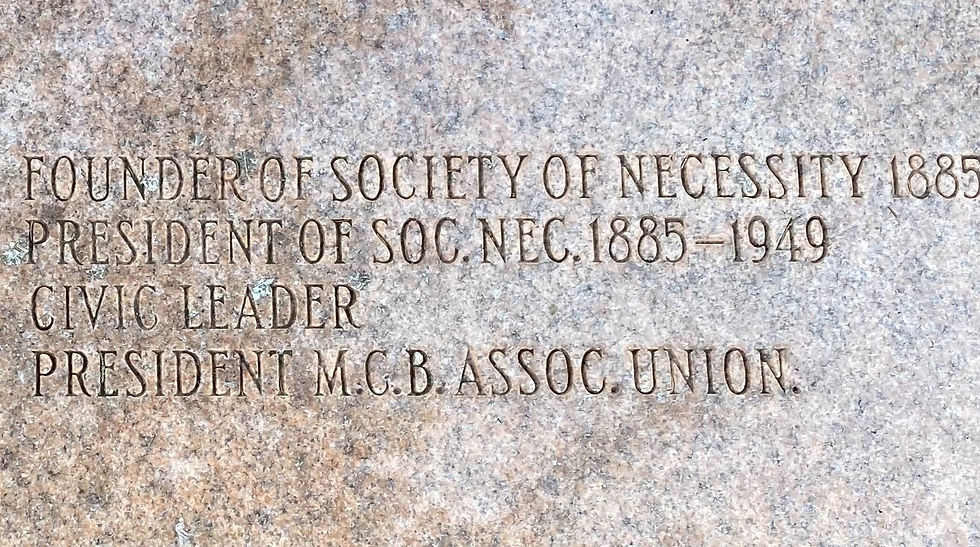

It took an enormous amount of courage and creativity for African-Americans to find their way during Reconstruction. While the Kingdom of the Happy Land was realizing its commitment to community living in Green River, another form of community was taking place in Flat Rock after the War Between the States along Mine Gap Road, now known as East Flat Rock. These people were primarily from Charleston and were accustomed to summers in Flat Rock. Following emancipation, they decided to stay in the mountains and were joined by other freed slaves. Like the kingdom people, the needs of this group came first. It was the same Happy Land ideal, “All for one, one for all,” that 20-year-old Henry Shields Simmons fostered with his 1885 creation of the Society of Necessity, a benevolent organization for freed blacks.

A Brief History of the Black Presence in Henderson County explains, “Admission into the Society required that a person be of ‘good moral character,’ pay an initiation fee of $1.00 and 10 cents per month thereafter as long as they were a member. An oath was administered stating: I agree to support and obey the constitution and by-laws of the Society of Necessity of Flat Rock, North Carolina, to which I have been elected a member, so help me God.”

The Society of Necessity acted as a safety net to support the local black community financially and spiritually. The organization provided small loans for whatever needs community members had for housing, food, sickness, death or legal services. Simmons served as president of the society from 1885 until his death in 1949. In addition to Simmons, 1903 officers included J. C. Markley, Robert Alston, L. G. Young, George and Lavenia Potts and J. H. Hallback. The society was developed and maintained like a functioning family; Lavenia Potts and J. H. Hallback served as mother and father of the group, both designations still currently appointed. Several of these officers were from families rooted in the Kingdom of the Happy Land, giving evidence to the migration of kingdom families into East Flat Rock.

George and Lavinia Potts, the mother and father of the Society of Necessity.

Photos by permission of Hortense Potts.

The heart of the Society of Necessity is Mud Creek Missionary Baptist Church. In 1867 many of the freed slaves who had attended services at St. John in the Wilderness and Mud Creek Baptist Church decided to form their own congregation. Church members pooled their resources and in 1889 bought 1.5 acres of the Heidelberg estate (now Bonclarken) in Flat Rock and built their first sanctuary. In 1928, with the help of the Society of Necessity, the church bought the property where it now stands at the intersection of Roper and Mine Gap Roads in East Flat Rock.

Oakland Cemetery

The Sick Committee became a crucial arm of the Society of Necessity. People needed to know they could count on the care of the society when illness or death struck. According to the oral accounts of William Judson King, who was raised in the Flat Rock community, “The Sick Committee was responsible for the burial of the dead because no undertakers were available to blacks in those days. The committee would see to the funeral preparations. Members would bathe and dress the body, see that a coffin was secured, have the grave dug and the body lowered. Oakland Cemetery was owned and tended by the Society of Necessity, and any member of the society could buy a plot for the sum of one cent per square foot. In 1942 the price was raised to two dollars and in 1964 to six dollars.”

Recently, my husband, Sandy, and I visited Oakland Cemetery. Located on Highland Park Road between Highland Lake Road and West Blue Ridge Road, it is the cemetery for members of the black community in East Flat Rock and Mud Creek Missionary Baptist Church, and one of the most historical cemeteries in Henderson County. As I walked through the graveyard, a spiritual presence embodied the site — it was powerful. Familiar names — Markley, Potts, Simmons, Darity, Edwards — recognizable as the pioneer black families in my research marked the tombstones of these significant and brave souls. Tears filled my eyes as I scanned dates and occupations — blacksmith, midwife, soldier — recalling their stories. White crosses marked the graves of unidentified people, most of them born into slavery, some members of the Kingdom of the Happy Land and their descendants.

Henry Simmons was a visionary and an intelligent person who believed in hard work and helping others. When he started the Society of Necessity, it was just the beginning of his lifelong commitment for the betterment of his community. With an avid interest in the law, Henry spent countless hours at the Superior Court of Henderson County taking notes and studying cases. He counseled his community on the importance of deeds, wills and records. He bought up land around Mine Gap Road and helped new community members with the purchase and building of their homes. When the Quakers showed an interest in starting a school in East Flat Rock, Henry was the driving force behind it. During the summer months, he operated a cannery and employed many from their community. When winter came and food was scarce, Henry had a cache of canned goods to share. Henry’s living legacy is the Society of Necessity.

John Calhoun Markley (1848-1921) and his wife, Sally Darity Markley (1854-1959), were former slaves who moved to the East Flat Rock community by way of the Kingdom of the Happy Land. Sally Markley was the daughter of Logan Darity, a Cherokee abandoned as a baby on the battlefield and raised by white settlers. “Aunt Sally” as she was called, became a renowned midwife and granny doctor within the community. John operated a blacksmith shop with his two sons on West Blue Ridge Road beside King Creek. John was also the first mail carrier for Flat Rock as well as a farrier, and his son Jim served after him. Sally and John Markley had eleven children who survived to adulthood.

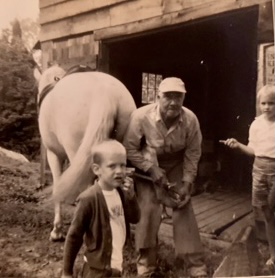

(Left) Jim Markley shoeing Lady Jane, a horse of Alice Andrews, whose grandchildren look on, photo courtesy of Alice Lee; (right) a rendering of Merkley's Blacksmith Shop, photo by permission of Historic Flat Rock

The Markleys were known for their blacksmith shop that served generations of year-round and summer Flat Rock residents. “They shod horses, shaped plows, fixed wheels and spun light-hearted tales of “homespun philosophy” in the process,” author Alice Sink said in her book, Hidden History of the Western North Carolina Mountains. John Markley died in 1921 at the age of 73. His two sons, Garfield and Jim continued the blacksmithing business. After Garfield’s death, Jim operated the shop until the mid-1960s when failing health forced him to close. His mother, Sally, had a stroke in 1953, but despite doctors’ expectations she lived to be 104 years old, “chewing tobacco and eating peppers and onions.” Both John and Sally Markley along with some of their children are buried in Oakland Cemetery.

Wanda Horne is among a handful of parishioners who still attends services at Mud Creek Missionary Baptist Church. Her great-great-grandparents, Caesar (1825-1931) and Venus Grant Edwards (1820-1895) came to Flat Rock each summer from Charleston with the Ralph Izard Middleton family. They were married on June 9, 1855, at St. John in the Wilderness Episcopal Church in Flat Rock. Church records show they were the first slaves to be married in the church. After emancipation, Caesar and Venus remained in the area and became founding congregants of Mud Creek Missionary Baptist Church and the Society of Necessity.

Emmie Hortense Potts and her sister, Frederica Potts Sayle, live in the house their parents, Fredrick Henderson Potts (1885-1975) and Ethel Williams Potts (1896-1993) built on Mine Gap Road in East Flat Rock. The 1900 two-story house, Brook Ledge, was also home to her father’s extensive nursery and plant specimens. A noted horticulturist, their father worked as a caretaker, chauffeur and landscaper for Flat Rock estates and as a flutist with an Asheville symphonic group.

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak with Hortense by phone. After introducing myself, she immediately asked if I lived in a two-story white house off of Greenville Highway next to Kenmure. “Yes” was scarcely out of my mouth when she began telling me the most amazing story. As a child she accompanied her father to our home (owned by someone else at the time) to take care of the gardens. Her mother sewed and made curtains for the house. Years later she met my mother-in-law and went over to the house several times. She described it beautifully — even the old kitchen house. Her father was known for cultivating and planting native plants, particularly azaleas and rhododendrons, both prolific on our property. She remembered my mother-in-law coming over to get plants from her father’s nursery. She was sharp as a tack for her 94 years and totally captivated me with her family heritage. Her sister, Fredericka, is 101 years old and according to Hortense is “slowing down a bit.”

George L. Potts (1844-1926) and his wife, Lavenia F. Moultrie Potts (1846-1932), met at Glenroy (now Kenmure), the home of Dr. Mitchell Campbell King. They were married by the Rev. John Grimke Drayton, the rector of St. John in the Wilderness, on November 30, 1871, in the drawing room of Glenroy. George was the son of Clarence and Matilda Potts, slaves of the Davis family of Charleston. Lavenia was the daughter of Dr. Mitchell Campbell King and a King family slave, Charlotte Moultrie. Charlotte is buried in the Slaves and Freedmen cemetery at St. John in the Wilderness.

George and Lavenia lived in a caretaker’s cottage on the Glenroy estate. George farmed, supplied dray services and grew flowers, an interest he passed on to his son, Fred. In addition to being a seamstress, Lavinia was a midwife and herb doctor. She was known for traveling door to door selling her baked goods and delivering soup to the infirmed. George saved his money and in 1880 bought 82 acres atop Glassy Mountain where he built a two-story log cabin home. Eventually, George acquired 132 acres from the Kings for an average of $3 per acre. When the ancestral log cabin on Glassy Mountain was razed, Hortense rescued the hearthstone and had it placed in her garden at Brook Ledge.

George and Lavenia raised nine children including Hortense’s father, Fred, and John Moultrie Potts, father of the distinguished Southern scholar Dr. John Foster Potts (1920-2008). In 1889, the Pottses bought 50 acres of farmland in East Flat Rock along Mine Gap Road and built a two- story frame house there. George was a trustee of Mud Creek Baptist Missionary Church and the Society of Necessity. Lavenia was the first designated “mother” of the Society.

Fred Potts bought his homestead in East Flat Rock when he was a teenager working in Asheville. “My parents were very proud, hardworking people with clean livers,” said Hortense. “I’m especially proud of my father. He never met a stranger and could talk the horns off a bull! He had little formal education, but he became a well-educated man. He knew all the botanical names of the plants and flowers.”

Education was stressed in the Potts family, particularly by their grandmother, Lavenia, who learned to read and write while she was a slave. Both sisters earned undergraduate degrees from Bennett College, and Hortense went on to get a master’s in education from Western Carolina University. She taught school for the majority of her adult career, and Fredericka worked as business manager of Bennett College in Greensboro.

Hortense said their old neighborhood has changed during the years, but they still have fond memories of family, friends and their church community. “People here, both black and white, have always been close and shared what they had. One year during planting season, my father’s tractor broke down. He was on a time schedule to get his crops in the ground. One of our neighbors, a white man, came over and plowed the field for him and helped him seed it.” Hortense and her cousin, John Potts, continue to carry on the traditions and legacies of their community, including the Society of Necessity, a 136-year-old charitable work that continues to play an important role in the East Flat Rock community today.

Resources:

The Kingdom of the Happy Land by Sadie Smathers Patton

Flat Rock, the Little Charleston of the Mountains by Sadie Smathers Patton

A Brief History of The Black Presence in Henderson County by The Black History Research Committee of Henderson County with Gary Franklin Greene

From the Banks of The Oklawaha Vol.1 by Frank L. FitzSimons

Hidden History of the Western North Carolina Mountains by Alice Sink

Glimpses of Henderson County North Carolina by Terry Ruscin

East Flat Rock Family by Pete Zamplas in Times-News, Feb. 25, 2001

The Potts Family Legacy by Terry Ruscin in Times-News, Feb. 26, 2018

Flat Rock’s Society of Necessity by Beth DeBona in Times-News, Feb. 21, 2016

Glimpse into the Past by Joel Burgess in Times-News, Feb. 1, 2004

National Register of Historic Places, Flat Rock Historic District

Henderson County Genealogical and Historical Society

Missy Craver Izard was born and raised in Charleston, South Carolina. She resides in Flat Rock, North Carolina with her husband, Sandy Schenck, where their family runs a summer camp.