Remembering Thomas Heyward of 18 Meeting St.

- Apr 25, 2024

- 5 min read

By Peg Eastman

Thomas Heyward, Jr. was one of four signers of the Declaration of Independence from South Carolina. His memory is perpetuated mainly because of a house museum on Church St. at the residence he enjoyed in the 18th century, proving once again that bricks and mortar are the most enduring reminders of historical events and people.

Born at Old House Plantation in St. Helena’s Parish, Heyward inherited lands on the banks of the Combahee River, which he developed as White Hall Plantation. He studied law in London at the Middle Temple and was admitted to the bar in 1770. When he returned to South Carolina, he was admitted to the Charles Town bar and split his time between planting and practicing law in the city.

In 1793, Heyward married Elizabeth Matthewes, a regional beauty from a well-established colonial family; her brother John Matthewes also studied law at the Middle Temple, practiced law in Charleston and was a delegate to the Continental Congress (1778-1781) where he endorsed the Articles of Confederation. Matthewes was elected the 33rd governor of the state, serving a single term (1782-1783).

Heyward’s sister-in-law Lois Matthewes married George Abbott Hall, who served on the Committee of Ninety-nine for Charles Town, the First General Assembly and the 1776 Second Provincial Congress. The legislature appointed him a commissioner, to oversee the naval affairs of S.C. where he served until February 15, 1780.

Like his brothers-in-law, Heyward was active in local politics. He served in the last four royal assemblies (1772-1775). As the Revolution approached, he represented St. Helena’s Parish on the First Committee of Ninety-nine, which called for convening the First Provincial Congress. The voters of St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s parishes elected him to serve on the First Continental Congress. He replaced Christopher Gadsden when he resigned from the Second Continental Congress and joined the S.C. delegation with Arthur Middleton, Thomas Lynch and Edward Rutledge in signing the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

When young Heyward returned home, his father was reported to have expressed his indignation along these lines:

“A bold and precipitate measure, I think. Undisciplined militia like ours cannot stand against the trained armies of the king. We shall surely be beaten.”

“No doubt,” was the reply.

“What shall we do then?”

“Raise another army and keep up the struggle.”

“What, to be beaten again?”

“Certainly, and the same may follow over and over again; but we shall become reconciled to the evils of war and acquiring military experience, shall ultimately gain the victory.”

Heyward was a captain in the Charles Towne Artillery Company while his brother-in-law, George Abbott Hall served as a captain in the First Battalion of the S.C. militia when the British captured Charles Towne in May 1780. Even though they surrendered their swords and gave their parole so as not to offend the enemy, they were rudely accosted by the British officers with filthy remarks and insults.

In August 1780, Heyward was among 43 patriots whom the British sent to the Spanish fort at St. Augustine, Florida. Hall was in a group of 22 sent there in November. Heyward is reported to have been a cheerful fellow who boosted the morale of his fellow-prisoners with his jokes and mirthful songs. Meanwhile, his brother-in-law John Matthewes was in Philadelphia trying to get his kinsmen paroled. It took some months before those in St. Augustine were exchanged and transported to Philadelphia.

Back in Charles Town, the Matthewes sisters and their children stayed at 87 Church St. where they were forced to endure all types of privation; their misadventures have been passed down for generations. The violence took its toll: Lois Hall died in childbirth during the mayhem. In June 1781, George Abbott Hall returned to Charles Town to get passage for his sister-in-law, her son, and his numerous children. The family sailed to Philadelphia where they continued to work for the Continental cause.

The following year, Elizabeth Heyward was honored by Gen. Washington, who selected her as the Queen of Love and Beauty at a ball given in honor of the birth of the Dauphin of France. Throughout the vicissitudes, Elizabeth remained true to patriotic principles, but like her sister, the years of hardship caused her health to wane. She did not live long in exile and died in Philadelphia in the August of 1782.

Thomas Heyward returned to the Palmetto state after the British evacuated and married Elizabeth Savage in 1786. The couple spent most of their time on his plantation; he rented his Church St. town house to the city so that George Washington could stay there when he visited Charleston in May 1791. Heyward sold the property to John Faucheraud Grimké in 1794 (the Church St. house declined after 1865 and was later converted into a bakery; in the 1920s the Society for the Preservation of Old Dwellings got involved and the historic home was acquired by The Charleston Museum).

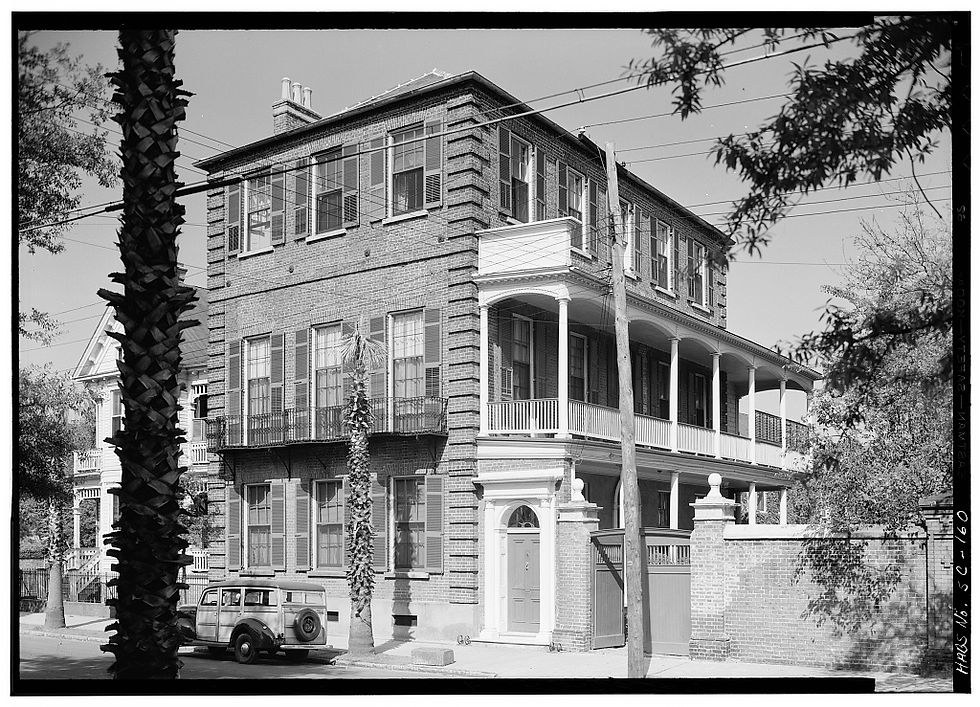

Heyward later moved to a three-bay brick single house on lower Meeting St. The deed transferring the “messuage and buildings thereon” from Nathaniel Heyward to his brother Thomas and his wife suggest that the mansion was perhaps built by Nathaniel Heyward prior to 1803. The brick quoins at the corners, classical door architrave and the iron balcony on the second floor add to the mansion’s elegance as do the oversized room proportions of the interior. The property still has the original arcaded piazzas, kitchen and slave quarters.

Heyward continued to be active in politics, serving in the Fourth through the Eighth General Assemblies. As a judge of the Court of General Sessions and Common Pleas, he helped establish educational standards for the S.C. bar. He was a member of the Charleston Library Society and trustee for the College of Charleston. He supported the federal constitution and was a member of the state convention which ratified it in 1788 and a member of the state constitutional convention in 1790.

Afterwards, Heyward retired from public life and devoted himself to his family and agricultural pursuits. He was the founder and first president of the Agricultural Society of S.C. and worked with them until his death on April 22, 1809. Heyward was buried in the family cemetery at the old house.

Heyward left 18 Meeting St. to his widow, who sold it back to Nathaniel Heyward in 1815. Two years later, Heyward conveyed the property to Nathaniel Heyward, Jr. and William Manigault Heyward in trust for his daughter Anne and her husband, Major Gabriel Manigault. She died in the 1850s and bequeathed the property to her children, who in turn sold the house and lot to James Adger for $20,000.

A Charlestonian by birth, Margaret (Peg) Middleton Rivers Eastman is actively involved in the preservation of Charleston’s rich cultural heritage. In addition to being a regular columnist for the Charleston Mercury she has published through McGraw Hill, The History Press, Evening Post Books, as well as in Carologue, a publication of the South Carolina Historical Society.